When my sister graduated from high school, my father took her to Paris, but the only details that emerged from the trip involved him snoring so loud she slept in the hotel hallway. So my image of Paris was a faded runner rug and my sister, curled in a ball at the foot of the door.

Ferg, Luke, and I arrive in Paris at 8am. Ryan, who’d gone to Spain for a family wedding, would meet us later in the afternoon.

We take the train to the metro to the basement level apartment we are renting for two nights. It is close enough to the sights to be convenient, and far enough away to feel like we are seeing the Parisian’s Paris. We drop off our bags, buy bread and cheese from the supermarche, and force ourselves onto the street, even though we are thinking, at home, it is 3:30 AM and I think I’d like to be in bed.

Several people have told us there are games in the Champ de Mars, the grass stretching out from the Eiffel Tower. Ferg herself had gotten into a game in the grass with a mix of tourists several years ago. We’re hoping to stumble upon something similar but when we get there, the main lawn is closed for repairs. When Ferg attempts to talk to the maintenance men, they ask her out for coffee but know nothing about the football.

On the side lawn, the only game is a swarm of French seven-year-olds who look like they’re on an Eiffel Tower field trip. While Luke and I love to play with anyone from old men to fat men to first-time females, we do not love to play with seven-year-olds. Something about sprinting past small children feels wrong. So Luke and I lean back against the bench and just watch. There’s an occasional game-ruiner who snatches it up with his hands and makes a break for it, the other kids tailing him until someone is able to knock it from his fingers and back down to the feet.

There is one drunk man with a Polaroid camera who wants to juggle the ball and kiss my cheek, but we opt out of a game with him. The only people left are either dozing or fondling lovers beneath umbrellas. Luke rolls the ball out in the grass and waits to see if anyone will take the bait but when no one does, we call it a day. It is not our mission to force people to play with us.

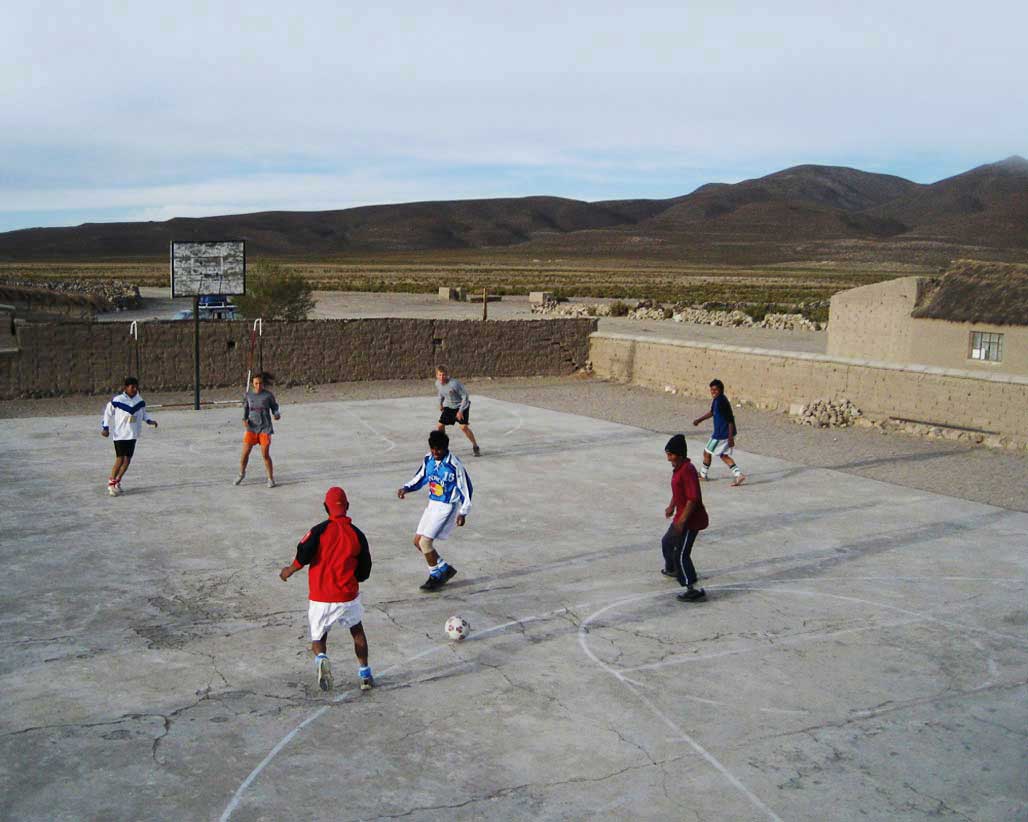

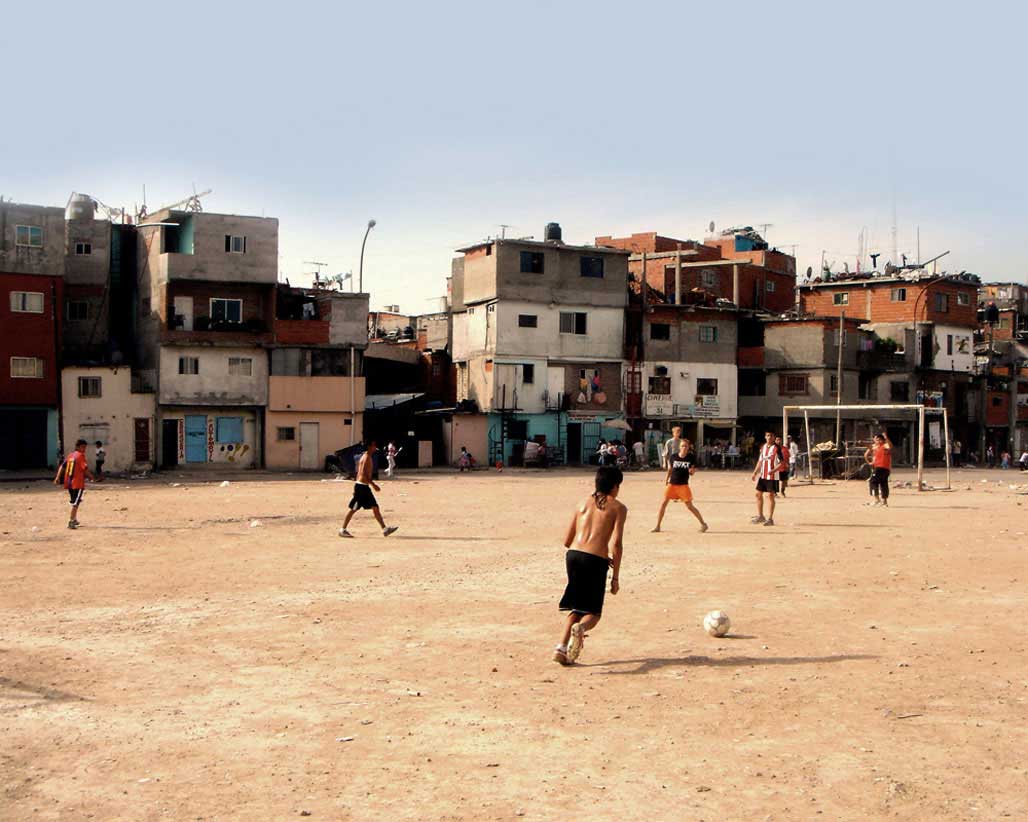

The beauty of pick-up is that it happens anywhere, with anyone, at no given place or time. This is also what makes it hard to find. When you are planning your trip, you go off the things you hear and the places people tell you games happen, but when you arrive, there is no guarantee that the Mennonites still play in the Bolivian jungle or that the lawn of the Eiffel Tower won’t be temporarily closed.

We walk six or seven miles home, soaking wet but warm, passing the Musee d’Orsay, the Champs Elysees, and the Louvre. We sit down at the Bataclan cafe on the corner across from the alleyway that leads to our apartment. The directions we gave Ryan are vague, and we are hoping to intercept him before he has the chance to get lost.

In South America, every bug, calamity, and illness found Ryan, so it’s no surprise to us when

we see him walking towards us, three hours late and without a bag. We hold up our hands and he mumbles, “They canceled my flight and lost my bag.” Bag contents included both eyeglasses and disposable contacts so our cameraman is now blind.

We regroup over dinner, heading to a restaurant Antoine, the man whose basement we are renting, recommended: “It is good, cheap, and you will like it.” The restaurant has soft light, stone walls, and photographs of memorable tombstones. The tables are close together and the menu is written on a rotatable chalkboard. We order two entrees to split-beouf de bordeaux and some sort of very good fish. As we wait for the food, I pull out my notebook and attempt to write out sentences in French I think we’ll need: Ou est le football? Nous faisons un documentaire sur le football de rue a travers le monde. Peuvons-nous jouer football avec toi?

When our waiter, Fabrice, comes over, he sits down with my notebook and re-conjugates my verbs, changes my articles, and adds accents. Before long, the whole restaurant begins to brainstorm on places we could go. The man to our right spends half his year in Chicago, and half his year in Paris. He tells us, “You are very lucky to have found this restaurant.” Fabriez sighs and sits down, “But Paris is like a museum, you cannot play football inside a museum. I think you will need to go somewhere else.”

The next afternoon we head back to the Eiffel Tower for one more try. The weather is better, the mood is lighter, and we know by now that what you find one day does not dictate what you will find the next.

The Champs de Mar has five or six squares of lawn and we decide to head further and further back, until we can see all of the Eiffel Tower in our camera lens. As Rebekah shoots a scenic and Luke and Ryan head to the bathroom, I scan the lawn for prospective players. I glance to my right and say, “Soccer.”

It seems too good to be true so I jog closer to make sure it is real and not some kind of mirage. There, to my right, is a soccer court, the Eiffel Tower shooting up directly behind it.

The guys to the side of the court waiting to get on look like French school boys-shaggy hair, reading glasses, dark jeans, backpacks. One of them looks like a gruffer version of Leo DiCaprio. He speaks English and explains to us that you play until two goals, winner stays on.

We collectively roll up our jeans and play. The guys are as good as anyone we played with in South America, and this comes as something of a surprise. In all honesty, we didn’t think the Europeans stood a chance.

My impression of the Eiffel Tower on our first day was rather underwhelming-swarming tourists, gray sky, and a giant metal structure around which no one played soccer-but today it is different: the sky is pink and the sun has fallen directly beneath the tower, giving the impression that it is lit from within. There are people all around, lounging in the grass, sitting on the steps, kicking soccer balls, walking hand in hand, living happily within the Paris museum.

On our way back to the apartment, a well-dressed French man mistakes us for Parisians and asks us for directions. Excited by the opportunity to say the one sentence I remember from French class, I say, “Je ne parle pas francais” and we continue walking. One hundred yards later he is still behind us, apparently heading the same direction we are. When he asks where are you from and why you are here, we tell him about our football documentary. He takes the ball from Luke’s hand and says, “Ah? You watch this.”

In his gray sweater vest, knit pants, and black shiny shoes, he starts juggling in the shadows of the cobblestone street.